One of the unusual features of American civil litigation is the “class action” lawsuit. In a class action lawsuit, one or several persons sue on behalf of a larger group of persons (a “class”). The rules of civil procedure allow this only when the issues in dispute are common to all members of the class, and the members of the class are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all into court. The decision in a class action lawsuit can bind all members of the class.

In the federal court system, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure apply. Class action lawsuits are addressed in Rule 23.

Situations involving class action lawsuits vary widely: from employees alleging a pattern of discrimination, to victims of a toxic spill, from consumers who purchased the same defective product, to patients who took the same unsafe medicine.

A class action lawsuit can also be filed on behalf of shareholders against a publicly traded company. For instance, Fannie Mae, more formally known as Federal National Mortgage Association, recently reached a $170 million settlement of a class action lawsuit accusing it of misleading shareholders before it was seized by the U.S. government during the 2008 financial crisis. The lead plaintiffs in this class action lawsuit are the Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Management Board, the State-Boston Retirement Board and the Tennessee Consolidated Retirement System. And among the many thousands of class members: Law Talk founder Drew Shagrin!

That’s right, I’m a member of the plaintiff class in this class action lawsuit. And I recently received in the mail a set of complex documents that would give me the right to receive a tiny portion of the settlement amount, surely less than the cost of postage from France to the US. I don’t intend to submit a proof of claim, but I’d like to share with you, dear reader, the documents.

For those of you interested in delving more, the case is In re: Fannie Mae 2008 Securities Litigation, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, No. 08-07831.

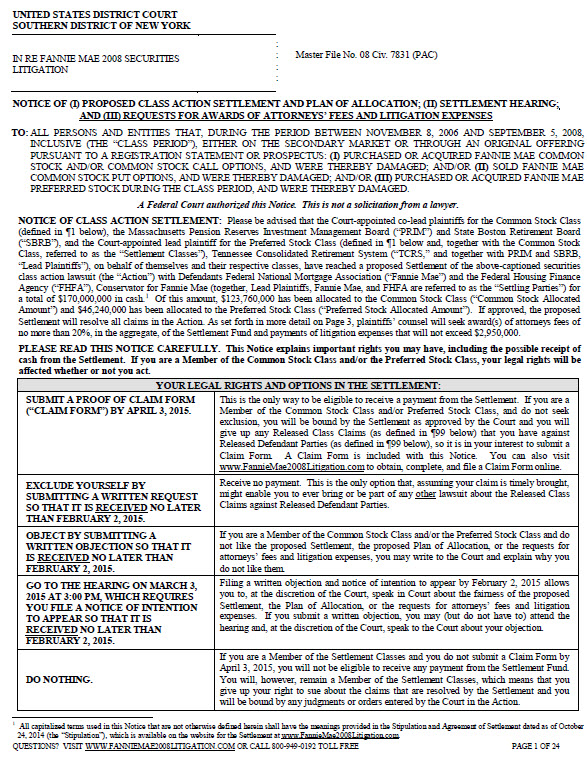

One of the documents that I received is a 24-page notice called NOTICE OF (1) PROPOSED CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; (II) SETTLEMENT HEARINGS; AND (III) REQUESTS FOR AWARDS OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND LITIGATION EXPENSES. You can read the entire document for yourself here. Or you can just admire its layout in the image below:

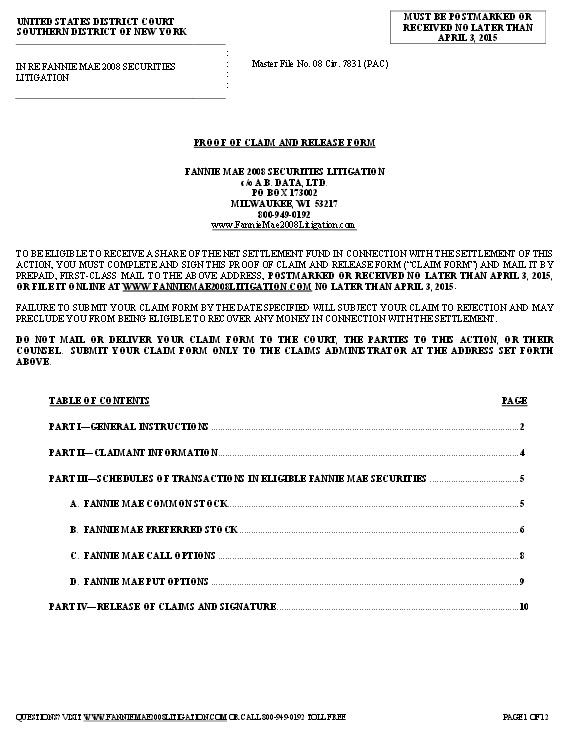

The second document that I received, called PROOF OF CLAIM AND RELEASE FORM, is only 12 pages long. You can read the entire document for yourself here. Or you can just admire its layout in the image below:

In the Fannie Mae case, it’s easy to criticize an approach that awards tens of millions of dollars in fees and reimbursed expenses to the lawyers representing the class, while I, a class member, can recover less than the postage cost in seeking a payment. So let’s look at a defense of class action lawsuits. This comes from the website of a well-known plaintiffs’ law firm, Lieff Cabraser:

Class action lawsuits are designed to advance several important public policy goals. A class action is often the sole means of enabling persons, even those with serious injuries, to remedy injustices committed by powerful, multi-million dollar corporations and institutions. As stated by former United States Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, “The class action is one of the few legal remedies the small claimant has against those who command the status quo.”

In other situations, each person within a large group may have suffered only limited damages and the cost of individual lawsuits would be far greater than the value of each claim. The total damages, however, to the class could be quite large. The wrongdoer would have the incentive to continue its fraudulent conduct but for a class action.

“In the age of mass production and mass marketing, class actions are necessary to allow individuals to take on multi-national corporations, where expenses of litigating would be otherwise prohibitive. The class becomes a de facto corporation for the purposes of suit, allowing individuals to band together and be equally matched against corporate defendants,” Lieff Cabraser partner and class action attorney Elizabeth Cabraser has observed.

Finally, where the defendant has engaged in a pattern of wrongdoing, a class action can provide an effective remedy for the group without incurring the costs of thousands of separate lawsuits and risking inconsistent decisions by the courts.

These are persuasive justifications. Now lets look at some criticisms. First, a class action can bind class members with a low award when they might have had a higher award in their own independent actions. Second, class members sometimes receive little or no benefit because of large fees for the attorneys. Alternately, some plaintiffs benefit at the expense of other class members. Furthermore, class action communications are confusing and can prevent class members from being able to fully understand and effectively exercise their rights. (See the Fannie Mae case notices above for proof of this!) Finally, class action lawsuits can undermine public respect for the country’s judicial system–they give the appearance, often based in reality, that the biggest winners are the plaintiffs’ attorneys, while increasing the cost of doing business.

Law Talk isn’t going to convince anybody that class action lawsuits are good or bad. (In fact, they’re both good AND bad.) The goal here was simply to introduce the reader to the concept.

May the law be with you!