French lawyers who work with American clients know that the American legal and business communities held their breath this past week waiting for the jury in a San Francisco courtroom to deliver its verdict in an employment-related lawsuit involving a legendary Silicon Valley venture capital firm. Today’s Law Talk helps French lawyers (and any other readers) understand what happened.

The defendant: Kleiner Perkins Caufiel & Byers, the VC firm that provided early funding for many prominent companies, including Facebook, Google, Genentech, and Amazon.

The plaintiff: Ellen Pao, a former lawyer who joined Kleiner Perkins in 2005 and was made a “junior investing partner” in 2007, and who was asked to leave the firm in 2012 (a few months after filing the complaint in this case).

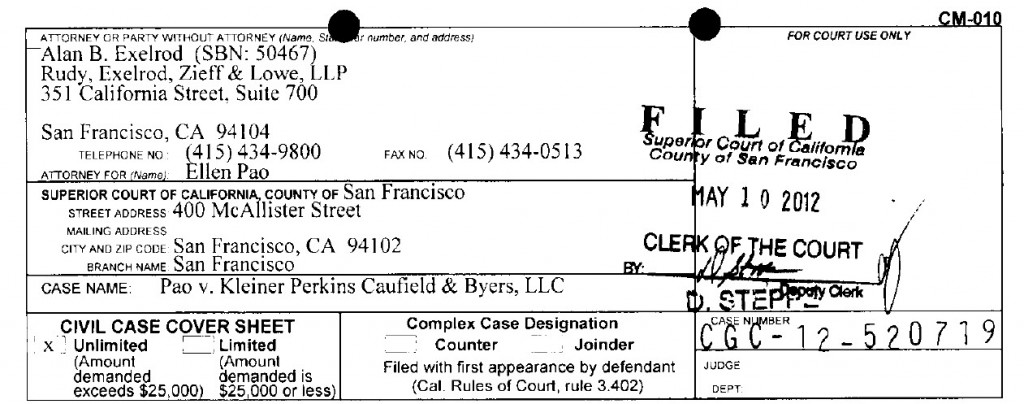

The complaint: In 2012, having been passed over for promotion to full partner, Ms. Pao filed a complaint in California Superior Court. The complaint asserted three causes of action: gender discrimination, retaliation, and failure to take reasonable steps to prevent discrimination, all in violation of California Government Code Section 12940.

The amount at stake: Ms. Pao had asked the jury to award $16 million in compensatory damages (based on the foregone higher compensation that she would have received had she become a full partner). For any finding of liability, the jury was also allowed to award punitive damages, which in theory would both reform this defendant and deter others from enaging in similar conduct. A typical cap on punitive damages in California is 9 times the amount of compensatory damages. Between the compensatory damages and the punitive damages, the amount at stake was nearly $160 million.

The jury vedict: Friday, nearly 3 years after the filing of the complaint, the jury delivered its verdict, specifically answering 4 questions. For each answer, the jury majority needed to be 9 out of 12, and the standard of proof was a preponderance of the evidence (ie, “more likely than not”). Here are the questions and in each case the jury’s answer:

1. Did Kleiner Perkins discriminate against Ms. Pao because of her gender by failing to promote her and by terminating her employment? The jury answered no.

2. Did Kleiner Perkins retaliate against her by failing to promote her because she had conversations with partners about the discrimination in December 2011 and/or because she gave a memorandum about the discrimination to the firm on Jan. 4, 2012? The jury answered no.

3. Did Kleiner Perkins retaliate against her by terminating her employment because of either/or her memo and her suit? The jury answered no.

4. Did Kleiner Perkins fail to take all reasonable steps to prevent gender discrimination against her? The jury answered no.

Some of the primary legal documents: There’s no shortage of commentary about this case (some of the better articles are listed further down in this Law Talk), but sometimes a lawyer just wants a direct unmediated look at the primary legal documents. We’ve gathered some of them for you:

Verdict form to be filled out by the jury (a distillation of the jury instructions, essentially an algorithm to guide the deliberations).

About the lawyers and the judge: They’ve been all over the American press lately, and you might be curious to know more about them. The lead counsel for Kleiner Perkins was Lynn Hermle of Orrick Herrington and Sutcliffe. Here’s her bio page on the Orrick site. (You might know some Orrick lawyers: since Orrick’s 2006 merger with Rambaud Martel, they have a Paris office.) The lead counsel for Ms. Pao was Allan Exelrod of Rudy, Exelrod, Zieff & Lowe. Here’s his bio page on the Rezlaw site. Co-lead counsel was Therese Lawless of Lawless & Lawless. Here’s her bio page on the Lawless website. The judge was Harold Kahn, named to the bench in 2002 by then-Governor Gray Davis. Here’s his not-very-informative Wikipedia page, and here’s a 2002 newspaper profile of him, shortly after he took the bench.

Interesting commentary: Now that the jury has issued its verdict, much of the recent press coverage has lost its interest, but here are two pre-verdict articles with enduring value. First, the New York Times magazine published an article on the industry background and what was really at stake. Second, the New Yorker magazine published an article on what we mean by “discrimination.”

What’s ahead: A complaint was just filed against Twitter, asserting gender discrimination. While the Pao v. Kleiner Perkins case was interesting, it was limited to one specific plaintiff. In contrast, the Twitter complaint seeks certification of a whole plaintiff class. (Go back and read again the Law Talk from early February on class-action lawsuits.) We’re going to hear a lot more about the Twitter case . . . .