A federal judge in California ruled a few weeks ago that Spanish law applied to a dispute before his court. He then applied Spanish law to resolve the dispute.

This wasn’t just any dispute, however. At the center of the dispute was a painting, Rue St. Honoré, après midi, effet de pluie, by French impressionist Camille Pissarro (the “Painting”).

The Painting is currently in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid. It arrived there indirectly as a result of the Nazi regime’s expropriation of art from its owner Lilly Cassirer Neubauer. The plaintiffs seeking to recover the painting are members of her family.

The court’s approach is in a sense a relatively straightforward one. First, the court had to resolve the “choice of law” question and decide whose law should apply to resolve the dispute before the court. Judge John Walter ruled that Spanish law should apply: “although plaintiffs’ relationship to California is significant, the painting’s relationship to California is not.” Having chosen Spanish law, the court then had to apply it. Judge Walter concluded that Spanish law wouldn’t require the painting’s return to the plaintiffs, because the museum “was not an accessory to the crime committed by the Nazis.”

Judge Walter also recognized that law and justice don’t always coincide. He ended his decision with an extraordinary recommendation in anticipation of an appeal:

Although the Foundation has now prevailed in this prolonged and bitterly contested litigation, the Court recommends that, before the next phase of litigation commences in the Ninth Circuit, the Foundation pause, reflect, and consider whether it would be appropriate to work towards a mutually-agreeable resolution of this action, in light of Spain’s acceptance of the Washington Conference Principles and the Terezin Declaration, and, specifically, its commitment to achieve “just and fair solutions” for victims of Nazi persecution.

The plaintiffs last Friday did in fact appeal the ruling, as Judge Walter anticipated. In the US federal courts, an appeal from a district court to the relevant circuit court of appeals is a matter of right—the court of appeals must review the appeal. (In contrast, an appeal from a federal court of appeals to the US Supreme Court is rarely reviewed—the Supreme Court selects only a tiny percentage of submitted appeals for review.)

An appeal typically addresses only issues of law, and not findings of fact. This appeal will lead to an exchange of briefs and then an oral argument hearing before a panel of three judges of the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The panel will then issue its decision.

Law Talk will come back to this issue when the Ninth Circuit acts on the appeal. In the meantime, here are a few resources for readers interested in learning more.

First, the decision by Judge Walter.

Second, a short Wikipedia article on Judge Walter.

Third, a series of articles involving this dispute and/or foreign restitution disputes in general, from the newsletter Art Law Report (published by the law firm Sullivan & Worcester) :

Fourth, Sullivan & Worcester lawyer Nicholas O’Donnell’s analysis of this decision, Cassirer and the State of Restitution—Takeaways and Next Steps.

Finally, Judge Walter’s presentation of the dispute (with most of the footnotes removed), to allow readers to fully understand the complex factual background, as well as the case’s procedural posture:

[Lilly Cassirer Neubauer (“Lilly”)] inherited the Painting in 1926. As a Jew, she was subjected to increasing persecution in Germany after the Nazis seized power in 1933. In 1939, in order for Lilly and her husband Otto Neubauer to obtain exit visas to flee Germany, Lilly was forced to transfer the Painting to Jakob Scheidwimmer, a Nazi art appraiser. In “exchange,” Scheidwimmer transferred 900 Reichsmarks (around $360 at 1939 exchange rates), well below the actual value of the painting, into a blocked account that Lilly could never access. After the war, Lilly filed a timely restitution claim. Because the location of the Painting was unknown, Lilly ultimately settled her claim for monetary compensation with the German government, but did not waive her right to seek restitution or return of the Painting.

Without Lilly’s knowledge, the Painting surfaced in the United States in 1951. In July 1951, the Painting was sold to collector Sydney Brody in Los Angeles, California through art dealers M. Knoedler & Co. in New York and Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills, California. The Frank Perls Gallery earned a commission of $3,105 for arranging the sale of the Painting to Sydney Brody. Less than a year later, in May 1952, Sydney Schoenberg, an art collector in St. Louis, Missouri, purchased the Painting from M. Knoedler & Co., on consignment from the Frank Perls Gallery, for $16,500.

More than twenty years later, on November 18, 1976, Baron Hans-Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza of Lugano, Switzerland (the “Baron”) purchased the Painting through New York art dealer Stephen Hahn for $275,000. The Painting was maintained as part of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Switzerland until 1992, except when on public display in exhibitions outside Switzerland.

In 1988, the Baron and Spain agreed that the Baron (through one of his entities, FavoritaTrustees Limited) would loan his art collection (the “Collection”), including the Painting, to the Kingdom of Spain. Pursuant to the 1988 Loan Agreement, Spain established the Foundation, a non-profit, private cultural foundation to maintain, conserve, publicly exhibit, and promote artwork from the Collection. The Spanish government agreed to display the Collection at the Villahermosa Palace in Madrid, Spain, which would be restored and redesigned for its new purpose as theThyssen-Bornemisza Museum (the “Museum”). On June 22, 1992, the Museum received the Painting, and, on October 10, 1992, opened to the public with the Painting on display.

Spain later sought to purchase the Collection. On June 18, 1993, the Spanish cabinet passed Real Decreto-Ley 11/1993, authorizing the government to sign a contract allowing the Foundation to purchase the 775 artworks that comprised the Collection. In accordance with Real Decreto-Ley 11/1993, on June 21, 1993, the Kingdom of Spain, the Foundation, and Favorita Trustees Limited entered into an Acquisition Agreement, by which Favorita Trustees Limited sold the Collection to the Foundation.[FOOTNOTE 5]

[START OF FOOTNOTE 5] In 1989 and 1993, in connection with the loan and ultimate purchase of the Collection, Spain and the Foundation commissioned an investigation of title to verify that the Baron and his relevant entities had clear and marketable title to the Collection. Plaintiffs claim that the investigation was incomplete and that Spain and the Foundation ignored red flags concerning thePainting’s provenance, including, for example, that: (1) the Stephen Hahn Gallery had been affiliated with Nazi looting; (2) paintings by Pissarro were known to be the frequent subjects of Nazi looting; and (3) the back of the Painting has a “Berlin” label traceable to the Cassirer Gallery and the provenance documentation provided no explanation for that label. However, this disputed issue as to the Foundation’s alleged “bad faith” is not material or relevant to the Court’s decision on these motions. [END OF FOOTNOTE]

The Foundation’s purchase of the Collection for $338 million was entirely funded by Spain. The Painting has been on public display at the Foundation’s Museum in Madrid, Spain since the Museum’s opening on October 10, 1992, except when on public display in a 1996 exhibition outside of Spain and while on loan at the Caixa Forum in Barcelona, Spain from October 2013 to January 2014. Since the Foundation purchased the Painting in 1993, the Painting’s location and the Foundation’s “ownership” have been identified in several publications including: (1) Wivel, Mikael: Ordrupgaard. Selected Works. Copenhague, Ordrupgaard, 1993, p. 44; (2) Rosenblum, Robert: “Impressionism. The City and Modern Life”. En Impressionists in Town. [Cat. Exp.].Copenhague, Ordrupgaard, 1996, n. 17, pp. 16-17, il. 61.; (3) Llorens, Tomas; Borobia, Mar y Alarcó, Paloma: Obras Maestras. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Madrid, Fundación CollectiónThyssen-Bornemisza, 2000, p. 156, il. p. 157; and (4) Perez-Jofre, T.: Grandes obras de arte. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Colonia, Tascnen, 2001, p. 540, il. p. 541. Declaration of Evelio Acevedo Carrero [Docket No. 249-2] at ¶ 18.

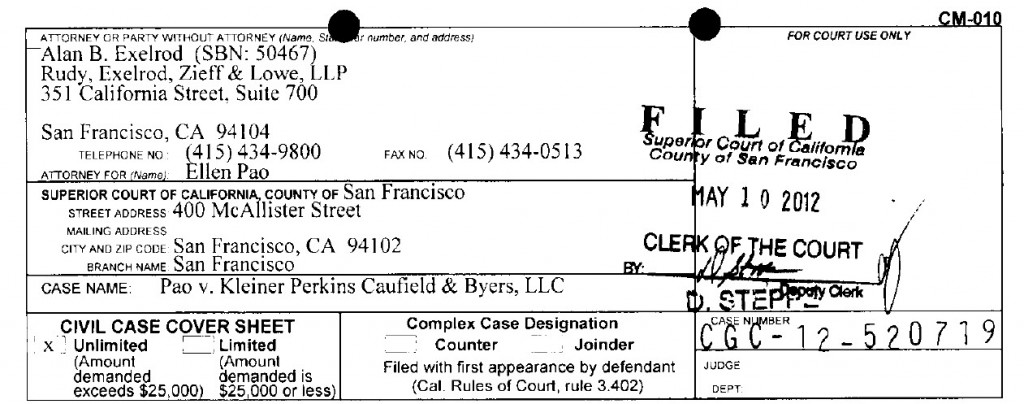

Neither Lilly nor any of her heirs attempted to locate the Painting between 1958 and late 1999, and Claude Cassirer, Lilly’s heir, did not discover that the Painting was on display at the Museum until sometime in 2000. On May 3, 2001, he filed a Petition with the Kingdom of Spain and the Foundation, seeking return of the Painting. On May 10, 2005, after his Petition to return the Painting was rejected, Claude Cassirer filed this action against the Kingdom of Spain and the Foundation, seeking the return of the Painting, or an award of damages in the event the Court isunable to order the return of the Painting. From 1980 to the time of his death on September 25, 2010, Claude Cassirer lived in California.

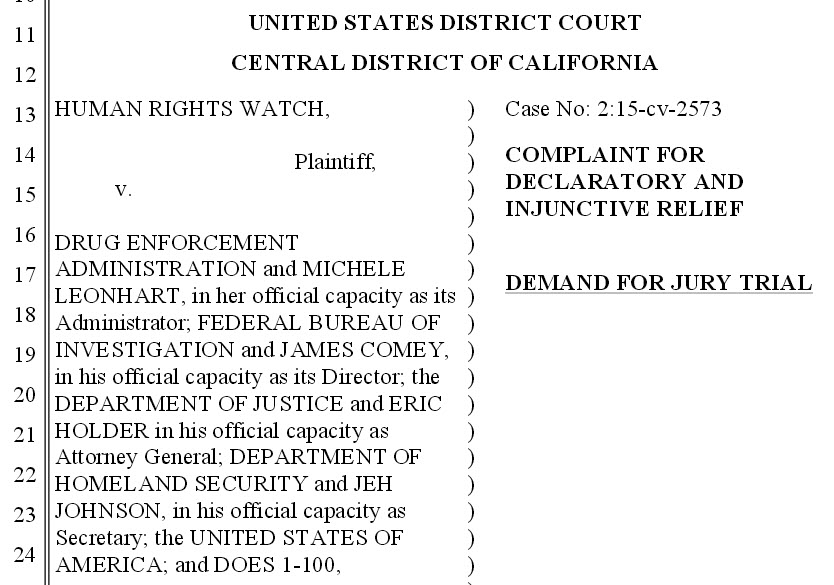

After extensive motion practice, including two appeals to the Ninth Circuit, the Foundation now moves for summary judgment on the grounds that: (1) under Swiss or Spanish law, the Foundation is the owner of the Painting; (2) California Code of Civil Procedure § 338(c), as amended in 2010, violates the Foundation’s due process rights by retroactively depriving the Foundation of its vested property rights; and (3) Plaintiffs’ claims are barred by laches. Plaintiffs move for summary adjudication, seeking an order declaring that the substantive law of the State of California governs, and that the law of Spain does not govern, the merits of this dispute.